To find something using the Google search engine, or a location using Google Maps, we simply type in a few words and then browse the results. This is so much better than what was available before that it has made Google one of the richest corporations in the history of the world.

However, many programs’ search functions still require you to enter the first name in this box, the last name in that box, and the gender in this other box. Faugh.

Users of Cerner, including their ED tracking system, Firstnet, are lucky as regards search (though perhaps not so lucky in other respects). There is indeed a set of boxes where we can type in a variety of identifiers (name, FIN NBR, MRN, CMRN, SSN, Birthdate, and/or Gender). But, we can simply type, in the “name” search box, either “Lastname, Firstname” or “Firstname Lastname.” Then, we are presented with a list of matches, with information such as SSN and birthdate, that we can use to identify the correct patient. Simple. Elegant. Fast.

The Google method – entering just enough information to get a good set of possible matches, then presenting them for review – has now been voted (by user’s choice of search engines) as the standard for searching. As Donald A. Norman says, if we want usable designs, we have to accept standards, even if we don’t like them, and since user expectations are molded by Google, we might as well resign ourselves to it.

There are other ways to make searching easier, and they are starting to become standards as well. Autocomplete is when the program predicts a word or phrase that the user wants to type in, without the user actually typing it in completely. This is effective when there are a limited number of possible or commonly used words, as is the case with most medical software. Autocomplete can speed up user interactions significantly, especially for those who type slowly.

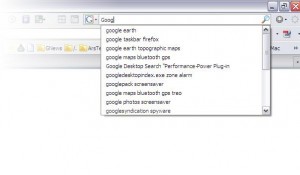

Autocomplete has been available for many years in some programs – for instance, the financial program Quicken, or Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. In these implementations, the autocomplete appears after the cursor as one types, often in grey, or may fill in multiple fields, as in Quicken. However, autocomplete is more familiar from the ubiquitous search engine Google, and the web browsers Internet Explorer and Firefox.

Google autocomplete gives the most likely match to what we type, with the number of results found. The autocomplete of the Firefox Search Bar matches searches that we have recently entered. The autocomplete of the Firefox Location Bar, nicknamed “AwesomeBar,” matches both recently viewed web pages and bookmarked web pages – and will return results sorted by frecency (an algorithm combining frequency + recency). It also will match what we type anywhere in the URL or description of a page.

Such searchbar smarts could ease our patient lookup – by using a frecency algorithm so patients we have recently cared for are presented as more-likely matches. It might also ease finding medications or discharge instructions. It would also help when you receive a call from an OB who says: “Someone called about 9 PM last night about a patient pregnant at 10 weeks with fetal demise, but I can’t remember the name, can you look through the patients from last night and see if anyone looks like that?”

***

January, 2015: a new fourth edition of “the polar bear book,” Information Architecture: For the Web and Beyond, came out a couple of months ago. If you are a developer of medical software, and don’t have in-house or consultant expertise in search, then I would recommend that you read Chapter 9: Search Systems, and Chapter 10: Thesauri, Controlled Vocabularies, and Metadata as a place to start learning about search. Driven by online consumer sales, search is now a big $$$ deal, so a lot is known about it. This is a good place to start, with references to other books and free online sources of additional information. For that matter, if you’re a developer, you should probably read all of the book, especially the chapters about labeling and navigation, as the labeling and navigation of medical charting and other apps traditionally sucks compared to the labeling and navigation, say, of amazon.com. Here is a place to learn.

And, if you’re into medical informatics, get the book and start at the beginning. Lots of useful stuff, and simply having read through the entire polar bear book puts you up a leg on those who haven’t. It’s a classic, and the Kindle version sells for under $10.

[asa]1491911689[/asa]

Tags: Cerner, Computers, ED, ED Systems, Emergency Department, Firstnet, frecency, Google, Google Maps, Healthcare, Healthcare IT, Information Technology, IT, Search