The following historical account is based on personal experience as a child being taken to ERs in the 1950s, as an observer in ERs in the 1960s, an EMT and then street medic training in ERs in the 1970s, and then as an emergency physician since the 1980s. Some names may have been changed or ambiguated to protect the innocent (or guilty).

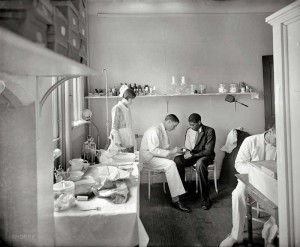

In the 1960s and before, the emergency room (“ER”) was just that – a big room, with some curtains to divide the stretchers. The ER was staffed by a nurse or two, and at the bigger hospitals, there would be more nurses and an intern or two, and maybe an upper-level resident would supervise from time to time. There was no standard of care, nor any quality improvement (QI) processes.

Gradually, medical technology improved, and we could do more (a lot more) for patients, especially in the acute setting. Primary physicians started referring (and deferring) patients to the ER rather than seeing emergencies in the office; indeed, now that emergency medicine is a specialty, many primary care doctors don’t think it’s appropriate for them to care for anything except minor emergencies in the office. Primary care doctors now don’t leave time each office day for add-on emergencies, as they used to back in the 1950s and 1960s. And ERs gradually morphed into busy, high-tech EDs, with lots of patients, and with nurses and doctors who specialize in emergency care. A standard curriculum in emergency medicine evolved, as well as postgraduate emergency medicine residency training programs for MDs and DOs.

But EDs became so busy that they made the job of an Air Traffic Controller look easy. And, as with air traffic control, specialized management tools evolved. Read the rest of this entry »