On May 3, Steve Stack, Chair of the American Medical Association (and an emergency physician from Lexington, KY) gave a presentation on electronic health records (EHRs) to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The paper is worth a close read. He observes that physicians are technology early-adopters, but that there had to be Federal financial incentives for physicians and hospitals to adopt an EHR. Why? EHRs suck. (I rephrase only slightly.) He points out that EHRs are immature products. If we judge by human development, and want to use a derogatory term, we might call them retarded, in this case invoking the original meaning of the word retarded, as in slowed development, compared to their peers.

Though an 18 month-old child can operate an iPhone, physicians with 7 to 10 years of post-collegiate education are brought to their knees by their EHRs.

In 2010, a quarter of physicians who would not recommend their EHR to others. Two years later, over a third were “very dissatisfied” with their EHR and would not recommend it.

When an EHR is deployed in a doctor’s office or hospital, physician productivity predictably, consistently and markedly declines. Even after months of use, many physicians are unable to return to their pre-EHR level of productivity – there is a sustained negative impact resulting in the physician spending more time on clerical tasks related to the EHR and less time directly caring for patients. In a way, it ensures the physician practices at the bottom of his degree.

He gives examples of how a physician’s medical note used to be:

- 24 y/o healthy male. Slipped on ice and landed on right hand. Closed, angulated distal radius fracture. No other injuries. Splint now and to O.R. in a.m. for ORIF.

- 18 y/o healthy female. Fever and exudative pharyngitis for 2 days. Exam otherwise unremarkable. Strep test +. Rx. Amoxil

He goes on to talk about how malpractice litigation, billing and coding, and CMS and other insurance requirements for payment have bloated the medical record. And further, how EHR features such as templates, macros, and cut-and-paste have homogenized medical records while (with the difficulty of typing or dictation) decreased the visit-appropriate essential information.

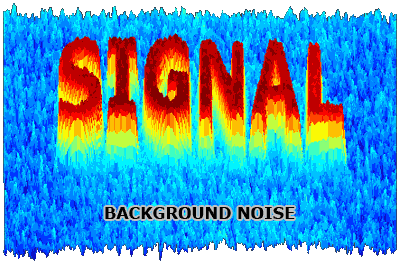

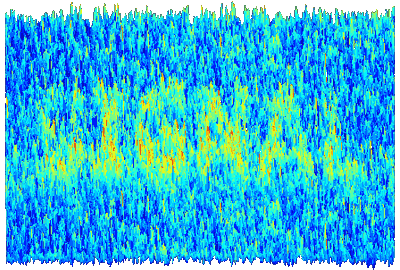

Seems to me that over the past 30-40 years (yes I’m that old) the medical-chart signal-to-noise ratio has gone from 0.99 (99% of the chart is signal, that is, clinically useful information) to, at least for EHR inpatient progress notes and ED notes, to 0.1 (10% signal, and 90% noise).

One of his three conclusions was

ONC [Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT] should immediately address EHR usability concerns raised by physicians and take prompt action to add usability criteria to the EHR certification process.

Bravo!