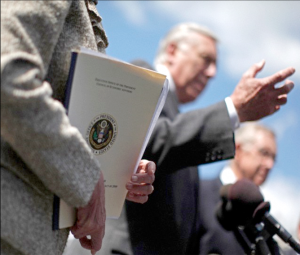

Nancy Pelosi holding the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

Meaningful Use has become a less-meaningful phrase in the USA over the past year or so, at least to those of us who work in the ED. Intentionally or no, politicians twist and deform the English language like no others. Their latest target, at least as far as Emergency Department computer systems are concerned, is the phrase: meaningful use.

In this post, I will grossly oversimplify to help provide a basic understanding of what meaning ful use now seems to mean and why you should care. As Bacon observed: we are more likely to reach the truth through error than through confusion.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) contains a vast wealth of provisions to reinvigorate the US economy (no pun intended). Of interest to readers of this site is that the ARRA says that, if you show new meaningful use of electronic medical records, then you can get money from the Federal government. However, this meaningful use only applies to office-based physicians and hospitals, so emergency physicians and Emergency Departments, by themselves, can’t get any money. However, in order for hospitals to get the money, the ED and the emergency physicians have to cooperate – which means you have some power over the administration. (Not too much, though – if you’re too uncooperative they can fire you or terminate your contract. Don’t laugh. It has happened.) Read the rest of this entry »